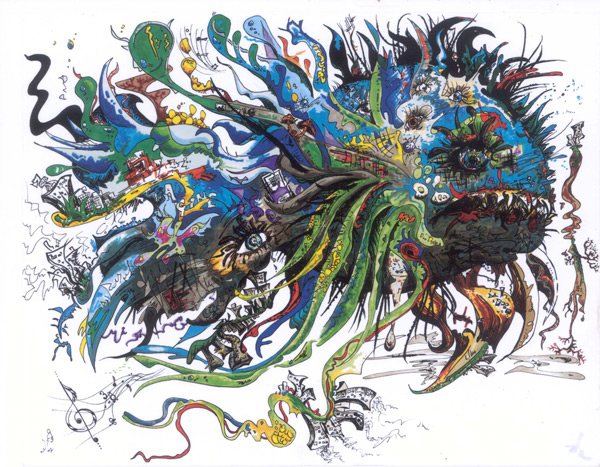

Nephilim

Lorelei Baughman

The sons of God saw that the daughters of men were beautiful, and they married any of them they chose.

Then the LORD said, "My Spirit will not contend with man forever, for he is mortal; his days will be a hundred and twenty years."

The Nephilim were on the earth in those days–and also afterward–when the sons of God went to the daughters of men and had children by them.

They were the heroes of old, men of renown.

He sat on the rise with his knees bunched under his chin, his wings torn and filthy behind him. Below, the water rose and swirled, mounting with that never ending rain, rain, RAIN. And the smell. Two thousand years of lousy sewage systems, goat food, myrrh, and whatever else had been building up to spin around in this shitstorm the Old Man had conjured up. You could see him up there, looking a little too self-satisfied when each new tsunami hit.

What a fucking fall. His wings were flopping and useless, and they had been beyond compare, tens of feet like luminous liquid mirrors. Now he looked like any other Earth-bound turd. He raged and bellowed, but the dying men near him were too fucked up to care - choking and spitting and screaming. Between the rain, storm, and the screamed pleas for forgiveness, the noise was unbelievable. They say that drowning is one of the better ways to die. Yeah, right. Tell that to these poor bastards.

The Old Man was definitely on a tear this time, very pissed off at all the whoring, gluttony, pride, whatever that the Watchers had been indulging in for the last long while. He'd been pissed before, but it looked like he'd actually been setting them up on this one. He actually planned this out. What didn't make sense was why everyone had to go. Ok, he was pissed at them, they'd betrayed a trust, but all of mankind? A bit of baby with the bath water if you asked him. You can bet that nobody was asking him, not now.

They'd been there when the Old Man had launched his Big Experiment, and that was one helluva of a week. He'd trusted them then, giving them a hand in his big creation-making. An ocean here, an acacia tree there. After that it had been a lot of work guiding, protecting, and trying to help the poor blokes (dust jockeys, Azazel called them) see above the day-to-day and hand-to-mouth. Helping the folks see that it just didn't work to sacrifice your kids, or kill their best cattle on an altar. There was such a thing as investment.

Not too much evidence of that now, as he watched a raft go by with a young guy who pitched an older couple over the side. He did recognize him, a trader in sheep futures.

Sepharim was gone now, along with Azazel and Araqiel. He'd watched them get flung down from way the fuck up there, their wings ripped from their bodies and tossed down after them like greasy food wrappers. No question about it, he had to think fast or wind up down in the whirlpool with them.

He struggled to his feet, his wings were saturated and dragging with an immense weight. As far as his eye could see, and that was pretty fucking far, were massive moving swells of dirty blue-black water that were tossing trees and people around like rubber ducks. Off to the right, way off, he could see the Old Man. He had to admit, that after that initial spate of lightening-throwing and staff wielding, he'd never seen the Old Man look so sad.

And it's fucking Noah that was the big answer to save the day. Turns out that the Old Man had Noah come to the Big House at the service entrance. Sepharim was definitely asleep at the wheel on that one. Noah snuck in at night like some back-door man, stinking of booze, and you know that the Old Man let that one slide.

He wished he'd just let it alone, but then he saw, smelled, and felt Persephone...

He hobbled over to the ramp along the side of the boat (weird to walk like this, his wings always kept him off the ground), the wind and spray nearly knocking him over. Up the ramp came CAMELS, GIRAFFES, PENGUINS (where the fuck did he get penguins?), two by two, boy and girl, very tidy. He saw Noah standing up on the deck with his family, and couldn't believe they were getting a ticket out, everyone else retching their last breath. You'd better believe the Noah family were no Aristotlean scholars.

Finally he saw a DOG, patiently waiting its turn up the ramp. "Where's your honeybun, Mr Canine?" he queried.

The DOG just looked at him stupidly. Dumb as a stump. Perfect.

Now came the hard part. Up they went, past the kid (who was reading a mystery), and off to the starboard side to their quarters. This was obviously the end of silky flax-spun bedding, just old straw and not too clean at that.

It was actually worse having the time to think. The last time he saw Persephone he could tell there was an extra life there, a tiny beacon of the best of both of them. Maybe somehow they'd survived, maybe. He'd go on forever, that was cold comfort now. Unfortunately, prayer was out of the question, he'd have to lean on hope. He put his muzzle between his paws, and tried to sleep.

Baneberry Fire

Jefferson Conner & Bennie Jones II

One night Brother fought Papa...fought him so hard, Papa stopped moving, stopped breathing, stopped drinking, stopped going to the Hookers, stopped scolding Brother. If that had been in the Coliseum, the crowds would cheer his name, but only I was left to applaud his work.

It happened on the last night in the motel, the same day I learned about how Julius Caesar died from Mrs. Walters. Julius was stabbed...so was Papa, although he saw it coming. Caesar didn't.

Papa and Brother were arguing again. Brother wasn't in his colors; he was in his clothes, although by his anger I would think at any moment he would strip down and begin to paint himself with chaos. Mama had locked herself in the bathroom because she was frightened by Brother, frightened by what he could do. I think she's just weak. Darla was trying to lose herself in our corded phone but it wasn't working, and I was crying, crying because Papa didn't like my drawing of Brother.

I knelt over it, the crumped piece of paper, colored bright with berries, just like Brother. The drawing was of Brother, standing in our color forest, with wicked red in each of his brilliant hands. Papa saw this when he came home, and beat me for it.

Brother came home and saw me curled up on the ground sobbing. He couldn't control himself. He first slapped Mama, demanding she tell him who did this, but she had been out, and Papa had already left to go live it up with his hooks. Mama hid in the bathroom, just as Papa came back from a night of drinking.Brother would show no mercy.

"You had no right!" Brother shouted, the anger rising in him.

"He's my son," Papa slurred as he tried to stand upright.

"You had no right!" Brother repeated.

"Oh shut up."

Brother pulled that knife, that oh so clever knife, from the pocket of that black coat of his.

"You had no right."

"The little shit is becoming like you; had to beat some sense in him,"

"You had no right."

"Put the knife down," Darla said finally, hanging up the phone.

"He won't do it, he's spineless just like his Father."

Brother screamed, although I couldn't be sure it be could considered a scream as it broke all rules of a scream. The sound made my body rattle, the yellow of our room turn white, and filled Papa's heart with fear. I looked up, through tears, and saw Brother lunge forward...

Red. Red was his favorite, and red was what spilled out onto that yellowed carpet of our overly yellow motel room. It wasn't like the wicked red of fire that burns without judgment, or the red that lights up the skies at dusk; no it's more like the thick, dark, heartless red of hatred. The red that you can't really see, the red that you can feel. Julius Caesar bled that hated red.

Darla shrieked, my tears stopped, and Brother smiled. It was a smile that matched the ones he flashes at me once a tree is liberated. Brother's body moved quickly, as Papa fell to the ground in a pale heap. The knife was removed, and heated eyes fixed on Darla, poor, defenseless Darla.

More red, more hated red. I didn't like this red; no, I liked the blueberry blue better, the blueberry blue that came from Brother's eyes as he moved across the room to reach for his half-sister's neck. I could hear Mama howling from the bathroom; I had a feeling she knew what was happening. I sat back beside my crumpled painting of Brother, and watched him work without too much sound.

"Please, please," Darla whimpered as Brother held the knife to her throat.

"Yes, I burned the fucking house down."

"Please, don't, I'm sorry."

Brother smiled again, hated red in his teeth, "You disgust me, you vile commercialized pig. Give me a reason why I shouldn't end you."

"Brother, please."

"Give me a reason!" Brother shouted, pressing the knife harder against her overly colored skin.

"I'm your sister, please stop."

Tears wiped away the fake colors, and made them run.

"He is my only family," Brother spat pointing at me, "He is the only one who understands me, who is willing to listen...None of you listen, you just eat, shit, fuck and die,"

"I love you Brother. Please stop this, I don't want to die," Darla pleaded, the tears streaming like a river now mixing with the beginnings of that hated red; a bit of it was Papa's.

"No-no I'm not your brother, you are not my sister. You're cattle, nothing but blind stupid cattle."

More hated red, more screams; this was unlike liberating trees. I wanted to run, to scream, but this was Brother, brilliant, wholesome, genius Brother. I could not run, not now. Mama had locked the door, and Brother swore for it; another painting for another time I suppose.

Without any more people to be liberated, Brother went for his neon orange bag of berry paints. Tossing some of Papa's cash in the bag, and a few bottles of water, Brother caught my wrist and dragged me from the yellow-red motel

We stole Papa's blueberry blue sports car, and before long were tearing back to the edge of the "gray-lands". When we reached the end of that barren and colorless wood, the sun was rising again. Brother said a lot of things, some of them I remember, others I don't.

"Keep that blood close at mind little brother, keep its color in your head. I want to remember it, I want to paint it, I want to liberate every tree with it. I want the world to know the sin of humanity; the true greed, petrified disgusting greed that has corrupted the roots of this earth. I want them to see, I want them to feel, are you listening."

"Yes."

"You better be listening, please listen, please listen. Colors, little brother, there are so many colors."

"Yes."

"You see don't you, you see the truth. Oh thank God, you see the truth; someone sees the truth."

"Where are we going?"

"Home, little brother. We are finally going home."

After that, Brother started rambling on about things I couldn't even begin to understand. At one point I had a feeling that he was talking to himself but Brother isn't that mad. When we arrived at our colored forest, the sun had cleared the trees and had set itself high in the sky. I followed him to the largest tree in our forest, the one Brother said hed never paint. Brother likes to lie sometimes.

He stripped down, and painted himself this time with red and only red. I watched, sitting on my hands against the trunk of the liberated tree painted with the word, Father. With quick hands, Brother painted the whole lower half of that enormous tree with the red of something Brother liked to call baneberry. To me it looked like strawberries, but Brother liked to lie, and I liked to believe him.

"Fire, the fire inside all of us, it rages, urges us to create, to inspire...Too many people ignore this fire, little brother are you listening!?"

I woke from a short nap and replied with a weary, "Yes."

"You're brilliant, little brother. Smarter than most, that's why Ben and Leah sent you to that school, why Ben didn't want you to follow me. I want you to continue being brilliant little brother, even after I'm gone, promise me that please, please promise me that."

"I promise," I blurted out, unsure of what would happen if I didn't.

Brother returned to his work, and I still had trouble making out what it was. He had begun to put gold into the painting, a gold that shined and dazzled; I had never seen this gold before. After a long while, he crafted a golden ring emerging out of this sea of baneberry red.

I dozed again, but was startled awake moments later by more of Brother's rambling.

"NO!" He shouted as he knelt down to my level and stared at me, his head cocked to the side like an owl.

"No, I will not join your army!"

I'm not sure who he was talking to, but I just replied with an honest, "Okay Brother."

"And I will not fight your war!"

He stood up straight and puffed out his chest.

"Do not fight in their war; do not fall for their army's lies,"

I glanced behind him, and saw that Brother had begun to paint a clock, a golden clock, spotted with droplets of baneberry blood.

"I am the fire, you are the fire; we are all the fire!"

Brother began running around the tree, screaming, "Fire, fire, fire," and laughing hysterically.

"They are fire, they have fire, but they will be burnt by the coming fire," Brother said, as he stopped running around and returned to painting.

"Is it almost done?" I asked.

Brother shrugged, "Has the world heard yet?"

"Heard what?"

Brother flashed me that smile, the hated red stained onto his teeth, "Heard of its sin."

I didn't reply, and just stared at Brother blankly.

"It's okay, you don't understand yet, you will,

He went back to his painting, and I went back to my sleep. I dreamt about Julius Caesar and Papa. In my dream they were talking in the forest, when Brother leapt out and set them both ablaze. Together, all three of them began chanting, "Fire, fire, fire." It was odd.

When I awoke again, Brother was gone, and the tree was all that I could look at for a long time. Brother had painted something there, something that is tough to shake from my memory. It was the image of a golden watch reading five till midnight, sitting in a pool of baneberry blood. This was one of Brother's best paintings, and it kept me wondering as to what it was and why he had painted it.

I waited for a long while, staring at the watch, hoping Brother would come bounding out of the forest to tell me more mad words and even madder promises. Eventually dusk set, and I was getting cold. I took Brother's neon orange backpack, threw it over my shoulder, and headed back to the 'gray-lands'. On my march out, the faces of the liberated trees seemed to watch me with anger, hissing at me as I walked alone. I took to running, the sense of betrayal burning my throat.

Once I was back out in the street, night had fully set upon me and I decided to wait a little while for Brother. Still no sign. The car was still there, which meant he was somewhere still in the forest. I took to walking along the forest edge, hoping he'd be waiting for me.

The night was thick, as the moon had decided to hide for the evening, so I found myself stumbling as I walked along the tree line. After patrolling didn't work, I went to calling out his name, a name I hardly remember. Still no reply. A few neighbors spotted me, while they were either out walking their dog, or going for a late evening jog. Some wanted to help, said my mama was probably looking for me, but I was sure to tell them off like Brother would.

"Don't you have something better to do," I'd hiss, or "Fuck off." That was Brother's favorite to use on people. I slept in the car that night, covering myself with Brother's backpack and wondering what could've happened to him. My dreams were fogged with that hated red, and of Rome, or was it Roan? I can't remember. The next morning, I ate at some granola he had packed especially for me. Once I was mildly full, I went back to the tree where Brother had painted the bleeding watch.

I saw something perched on the branches. I thought it was a bird, but birds didn't hang upside down. They weren't that big, either.

When I dared to take a closer look, I saw the blueberry blue of Brother's face, the hated red still in his teeth and the blank gray of his eyes.

I watched him hang from that tree, with a rope wrapped around that slender red neck of his. I wanted to climb up and be with him, join him in that faraway place he always dreamed about; he did say you couldn't get there by plane.

Without too much sound, I went to the neon bag, retrieved Papa's beer, and poured it at the base of the tree. Then with careful hands I lit a match, and watched the fire spark to life; such beauty in something so terrible. Brother would've wanted it like this.

Standing back, I admired my work; the textures of red, white, and gold. Not quite white, not quite yellow, but something in between. Satisfied, I turned from the bleeding tree, and stumbled past the faces who now watched with a sense of pride.

When I passed the final tree in our colored forest, my body locked up, and I wailed in pain, a terrible, terrible pain. I felt like Julius getting stabbed, like Papa getting stabbed.

Red was Brother's favorite. Red that lit up the sky when it was time to go Home, or the wicked red that turned things gray, or the hated red that spilled from people if you press hard enough. Red is my favorite, too. Wish I could tell Brother that...

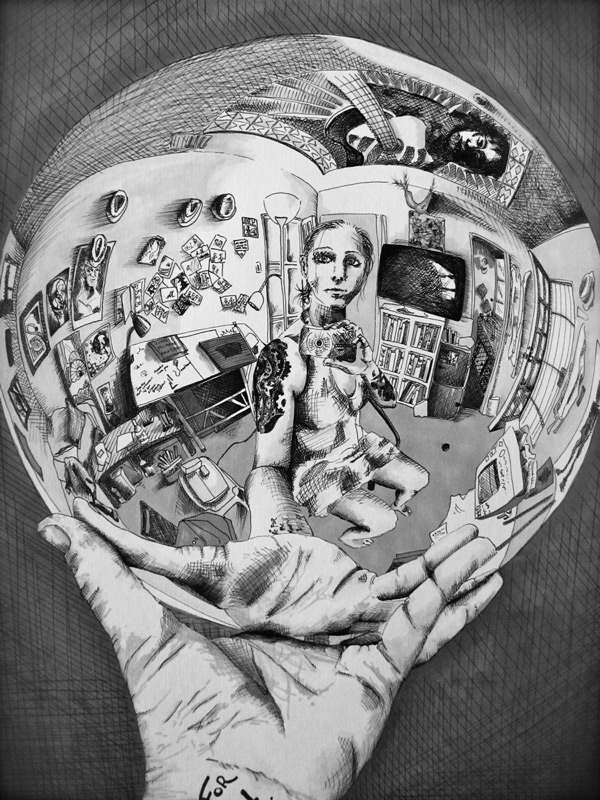

Inside Voice

Kyle Della-Rocco

Why is this in the soup aisle? Tom puzzled as he picked it up, noticing on the back that the instructions for the toy were in Chinese. He wondered why this could be as he strode through the store, passing by several children and parents. He set it down on the white metal shelf above its little red placard, and noticed it was the last Buzz Lightyear toy.

He turned to head towards the back of the store again, but couldn't help but watch as a boy swaddled through the store, the bulbous fat jiggling out from under his too small t-shirt. Tom moved aside as the boy walked up to the toy. The father walked by Tom and briefly acknowledged him by nodding. The father made his way to his son, shoving him forward several feet. Tom started to walk away, but then heard the loudest sound coming from behind him. The sound was a piercing shriek, almost like the sound a dinosaur would make in a movie.

Tom turned, shocked to see the portly boy screech at his father, "I want it!"

The father looked at his child, "Jeffrey, I told you, we can't afford it." The boy squawked out facts and figures about the action figure in his hand. Tom could see the father sweat and his face became a tomato red.

"It's the best, I love Buzz Lightyear, buy it!" He could see the father's hand shaking, as the father moved it up to strike. Tom wanted to move forward, but his feet didn't want to listen to his commands.

The father stopped his hand, "Jeffrey, we're leaving."

"NO!" The boy planted his feet firmly on the ground. "I'm not leaving, you can't make me."

Tom heard the loud smack, saw the red mark on the boy's cheek; he could feel the sting. Tom felt ashamed, as if he should have intervened. He saw the man's face shift, his eyebrows unfurrowed as he broke out into a smile. Tom moved a little bit closer, but stopped himself, unsure of how he should act.

"Ha ha," his hand struck the child again, he laughed. "Jeffrey, you're my son and you will do as you are told." Tom wanted to do something, to say something, but an invisible force steadied him, kept him still. He watched the father heft the load onto his shoulder.

How is he still able to stand? thought Tom.

The father walked as a lumberjack would carry tree trunk, a wide grin on his face; a mechanic carrying a transmission.

"Where are you taking him?" Tom blurted out, almost feeling he overstepped his bounds as the father walks by with his load.

The father turned, almost banging his son's head into a shelf. "I haven't decided; meat packing plant, or his mother's..."

The Golden Abyss

Donna Dellinger

Yellowish light tried to shine through the greasy candle globe set on the table. It seemed to flicker with the thunder outside. Hamerin sat slunked over, lining and re-lining up his collection of shot glasses. The waitress named Maggie kept the whiskey coming, but for some reason, she never cleared the empties away. Perhaps she thought he needed them. Something to keep his hands busy. Certainly not to occupy his mind.

"Same Old Song and Dance" started playing. Hamerin had dropped coins for that song what seemed like hours ago. He lifted his full glass to a face of knots on the pine paneling and toasted, "To Rose." He brought the drink to his mouth, then tilted his head back sharply. The amber liquid ignited his throat as he swallowed. He sucked air through his clenched teeth; his eyes swam for a moment, and he closed them, reveling in the rush. When he opened them, he noticed that the glasses had doubled and immediately set his hands to straightening them, fingers going right through some.

Then the song cut out. He whipped his head around in the direction of the juke box. Two men were standing there. "Hey, that's my song," Hamerin shouted to them. He pushed out of his chair and walked over in shaky strides, teetering before grabbing the edge of the nearest table.

"We don't listen to that old crap, do we Ted?" said the bigger guy with a squared-off crew cut.

The other nodded. One of his rhinestone studs caught the light from the juke box and flashed neon blue.

"I used to play that song. Me and the band." Hamerin wavered, but stood tall.

"You can't play shit."

"No, look." Hamerin reached into his wallet and pulled out an old guitar pick. "And I'm gonna play again, too." He shook it in their laughing faces.

"Get lost, loser." Crew Cut grabbed for it, but Hamerin swung his arm away.

The pick slipped out of his hand. Hamerin bent down to get it and toppled to the ground as the two men muscled past. On his knees, he continued to grope for the fallen object. He thought he saw it peeking out from under the juke box. One long reach put his fingers into contact with its cool, plastic form. "There you are," he whispered. Then his body melted into the floor. It just felt so good to be one with the carpet.

There you are. The words seemed to repeat in his head as he lay on the ground with his eyes closed.

"I've been looking for you." But no, the words were definitely outside of himself. A female voice. He thought he felt a small jab in his side, like someone was prodding him with a pointed toe.

Hamerin looked up and the two heads above him became one. An attractive young woman was staring down at him. Her blond hair glowed like a halo, but her glinting ruby lips hinted worldly experience.

"I'm Deidre." She pulled him to his feet, then handed him a card as if presenting an ice cold Corona.

Through blurry vision, he read, DD's DD Service. "Double D?" He grinned.

"Turn it over."

Let me take you home, it said on the back.

"You are an angel." His grin became wider.

Deidre slipped an arm around his waist and walked him out. He felt the warmth of her body through her slickered overcoat.

Outside, colored lights pooled in the pavement, dazzling his eyes. Deidre helped him dodge the water that had collected in the pitted parking lot. The smell of rain filled the air, but the clear night sky signaled that the downpour had moved on.

With her arm still tightly around him, Hamerin fumbled for his keys when he spied his old pickup, then stopped, realizing it was her black Mercedes they were headed for.

That's okay, he thought. He would sit close, maybe nibble her neck, fondle her breasts while she drove.

"Wait – " he started as she guided him into the back seat.

"Shh," she said, pushing him the rest of the way in. She bent over him and fastened his seatbelt, her cinnamon breath brushing his cheek. Her lips should be there too. He leaned in for a kiss, kept leaning until he flopped over face first on the leather bench seat.

When Hamerin awoke, he was in front of his apartment, his angel still with him. His head pounded as she helped him out of the car. The cool night hit him in the face, and his headache subsided. He could see clearly now, and anticipation rose up inside of him as he studied the curves that had snuck out the front of her coat.

Together they climbed the few steps to his door. For some reason, Deidre was the one unlocking the lock...with his keys.

"So there they are." He tried to make it sound funny, but he realized it really wasn't. He frowned at himself for ruining the mood and tried to get it back by slipping his arms under her jacket and around her waist. He was surprised at how cold she had become. The slight chill in the air must have gotten to her. He would warm her up soon.

But she politely removed his hands, hanging on to one in a handshake. "Nice doing business with you." As they continued shaking, he thought he could feel the bones within her fingers, but that could have been the whiskey.

"My pleasure," he said. He swung the door open and entered first so he could get the light, then stopped when he realized that she hadn't followed. She was still standing on the porch, the booze making her look a little fuzzy at the edges.

"You comin' in?"

"No sir," she said. "I just need what's coming to me."

She started to come more into focus. The night was coming back to him. "I get it. DD. You're a designated driver."

"Yes sir."

"What do I owe?" he said, fishing out his wallet. "Never mind," he added quickly, grabbing whatever was there and putting it in her hands. "Take it all."

She sifted through the crumpled bills in her hand and pulled something out. "This too?" she asked, holding up the pick.

He snatched it from her hands.

"No," he said. "No, not that."

As she walked to her Mercedes, Hamerin turned the old guitar pick slowly in his fingers. The tiny embossed word was barely discernable to his touch: Rose.

He looked up and stared after Deirdre's taillights. Then he blinked, and she was gone.

The Face in the Box

Deb Ebert

Iceland. Iraq. Virginia. Indiana. I turn away from the picture of Uncle Roger. From all of these pictures. They need to go somewhere else, where the hard lessons go once you learn them, like when I touched a red burner for the eighth time, expecting something different to happen. I could write anything and no one would know the difference but me. I realize I have to start somewhere, anywhere. I return, forcing my legs slowly up each step as if I had just spent the last twelve hours in a classroom. When I look at my laptop again, I notice the light on the monitor had dimmed. All I see is the face in the box. I do not know my own story.

Debra Kay did not trust the word home and wanted to be far away from Indiana. She had earned a full ride to Indiana University and was considering the Air Force ROTC program that promised she would see the world when her closest friend suggested enlisting outright. She thought about it, concerned how much see wanted to meet Bobby Knight. It was not until she brought a history class study group to her house to work on a project that she decided she would, in fact, enlist. Debra Kay's mom welcomed every guest while they were there but scolded her daughter afterwards about bringing a black boy into their home. Debra Kay had heard enough. She was finished with the rants about colored music, black television, and the minority Olympic athletes. The very next day was her first meeting with the Air Force recruiter. He told Debra Kay about the wonderful things she could accomplish in the Air Force but warned that she would need parental permission. Back at home, she pleaded with her mom. This was peacetime after all, what could happen to her? Her mom relented. Twenty four weeks later, Debra Kay was on her way, bound for a much bigger place than Hanover, Indiana, full of people different than she ever known.

Life was not fair for Airman Ebert. She had only once called Master Sergeant Sacco a dumbass to his face before throwing up her hands in disgust and huffing right at him. She could not help her lack of filter this time; he refused to answer a single question of her about Air Force history, and she needed to prepare for the promotion exam she had in two weeks. The additional duty was a punishment. Airman Ebert was reduced to shivering in a cold dark guard booth for twelve hours watching planes that would not move. Everything was silent. On the tarmac was her favorite aircraft, an E-3 AWACS. She had just taken a familiarization ride on it. There was a rotating radar on top. A was a beak sticking out of the windshield, and she enjoyed an emergency layover in the plush green countryside of Scotland. There were no such colors in Keflavik, Iceland, where she was assigned. Only five shades of gray: the darkness of the mountain, the brightness of the snow banks, the dinginess of the slush, the bleakness of the buildings, the heaviness of the clouds overhead. And the cold seemed colder. Iceland was not supposed to get this cold. Thirty below zero. Thermometers shattered at this degree. She stomped and clapped under the three layers of clothing under her uniform and her black toboggan hat. Airman Ebert could see her breath and tried to clock when the vapor turned to ice. Her eyes moved and her breath caught. Stars peeked through the greens, blues, and reds that made the sheets of light that shimmered off of the Atlantic Ocean. She felt like she could reach up and touch colors her eyes had never seen. Her hands moved in different directions. She tried blending the colors but the yellows, purples, and oranges moved around her of their own accord. She could hear the deafening crackle around her and nothing else. Nothing was cold anymore.

Debra had two Dobermans, was a marksman with her Glock 45, and well versed in three forms of martial arts but still double checked the doors and windows every night. The only mild relief she got was when Uncle Roger visited. She hated Virginia and the fact that she was a civilian again; he knew it and made a point to make special truck runs from his home base in Indiana to check on the twenty-seven year old who grew up calling him Dad. In this man's presence Debra was safer and he had made it so ever since it was clear his sister did not want a third mistake. Debra had seen the photos of her mother, brother, and sister sitting happily at Grandma's. She had her own picture of that time: Uncle Roger and her, smiling blue eyes sparkling from both occupants of that early eighties orange couch. The second time Uncle Roger visited Debra's Virginia rental, he immediately questioned the glossy, nothing-is-painful look in her eyes as well as the near empty bottle of painkillers on the entertainment center. Debra assured his narrowed eyelids that she had just come in and had left her sunglasses in her truck. It was a half-truth that kept her eyes from meeting his. It had already been discovered that year that Uncle Roger had developed a heart problem, and Debra would be damned if she made it any worse. He had to know she was fine. Debra left to go to the grocery store to pick up the water he wanted, stopping for a refill.

I sit down again. The words are coming so fast now I can barely keep up. I haven't been able to buy a car, cook a meal, sit through a single class, or watch a movie without new images taking over and different words coming to mind. Edit this sentence. Change that point of view. Clarify this. This draft is more defining, but do I have that much-needed purpose? Theme? Goal? Right now I am supposed to be memorizing facts from the Second Continental Congress for a test tomorrow. Writing is making me bipolar. One day I am pushing the images away and then I wake up again and welcome them. I think about what I want I really want to say and why I need to say it now.

Pepper loved April like a sane sister she had never known and was dismayed that she put her best friend into danger beyond comprehension. The two had met while inbound at the same time to Barksdale AFB in Bossier City and bonded instantly over their mutual love of the finely tuned craft of being a smartass. Pepper had gotten her name from April, who gave it to her because some random drunk guy who tried to introduce himself could not understand it when the Midwestern accent said Debra in introductions that took place in northern Louisiana. April convinced Pepper and Pepper convinced the Lieutenant Colonel and he convinced someone else to allow April on a deployment that included forward flights into the most dangerous city in the world in 2003. The seats in the back of the C-130 Hercules were configured so that the friends did not lose sight of one another. Pepper watched April's jovial reaction as they took off from a safe top secret location. The two young women flew with others, watching people they did not know until they entered Iraqi airspace and the cargo aircraft immediately went into combat mode. All lights in and on the plane were shut off, radar blips silenced, guns drawn from every crew member onboard, and not one person uttered another word. From the few tiny windows all they could see in the night as they began the descent into Baghdad was the red from the oil fires burning. April and Pepper were flung against one another as the plane unexpectedly banked hard left. The pilots circled everyone in, pulling G forces meant only for a fighter aircraft, and then banked hard right as stomachs entered throats. After more circles, the dark runway came into view of the aviator and the airplane nosedived with increased speed, leveling out and shooting flares into every direction a mere three seconds before the punishing firm landing that jolted every person aware. Within a fraction of a second of the wheels screaming to a stop, the back of the aircraft opened up, lights briefly came on and two among many were marshaled out at the speed of sound. Pepper glanced to April as the yells came to run for cover and the smell of gunfire and sight of tracers flying up into the sky engulfed everything they once knew. April had not even broken a sweat.

Debra overdosed and no one would care. She had said her final goodbyes to her Uncle Roger, military life, and too many pills. When she returned to Indiana after her aunt begged her, she could read everyone's mind. It didn't matter that she saw that man every night in her dreams or had to wake up realizing he was forever gone. It didn't matter that she was forced out of the only home she ever knew. Now there was something else, something that would stick forever: addict. Debra's aunt picked her up from the airport and drove her directly to Stonewell. Once they were behind locked door, alone with a single doctor, her aunt broke down. Debra listened as her aunt pleaded for her to have a better ending. Someone had to do better by Debra, especially Debra herself. After the interview, the doctor let Debra's aunt see her niece's new home on Stonewell's third floor. As they entered the bright hallway and the nurse's station came into view, another doctor, a nurse, and Debra's three new roommates emerged and welcomed her to a different kind of recovery.

It was eleven pm in Kirkuk on this cold December night. She worked so close to the perimeter that she had to race in complete darkness towards any cover when the shelling started. Ebert reached the terminal to find that the C-17 she was hitching a ride on would be delayed for hours. She wondered what the holdup could be. Ebert boarded the flight after all of the other occupants and when she saw the space that was left for her, she had to look away. It was the only seat left, the one next to the box. The box that was on its way home where the people of the person inside would claim it and put it in the ground and say a few words that might mean something. Who was in that box? She tried to imagine his face. She was sitting so close she could reach out and touch the stars and stripes. Did he take a bullet that was meant for her? What was his last expression? Nothing made sense to Ebert, other than the fact that they all were on a homebound flight with different destinations.

I used to be your property. No move was made without your consent. You gave me friends and then took them away. You blamed me for your mistakes and took credit for what I did right. You took my identity and robbed me of my voice so that you could say whatever you damn well pleased. Whenever I did try to speak, you said I asked too many questions and forced me nose-first into a corner. I broke by back, shoulders, and spirit for you. You don't acknowledge me any more even though you still prosper from my efforts. My face is just one of many and you do not care. I have news for you. I am better off without you in my life. I have a voice now. You would do well to remember that. There are no more corners to shove me into or blame to hand my way. I have untangled myself from you. I am free.

Apples and Bananas

Raquel English

EVIE

I've been coming to this same grocery store for five years, and each time I suffer the same dilemma: apples or bananas? I'm pretty sure I've broken the world record time for staring at fruit. It's just that every time I reach for one or the other it's like a rope yanks back my wrist. Shopping shouldn't be this hard

Both bruise equally and lose their taste over time, I already know this. They're even marked at the same price today so that doesn't help. It just has to come down to which one I want more, I guess.

The bananas are curved like a smile full of genuine sweetness. But they're strong too, protected by a durable peel. The perfect combination of outer strength and inner sweetness. That's what a banana is.

But then you reach for one, and the stem stabs you in the hand. You try to grab it to peel the banana open, but it won't open. No matter how much you try, the peel remains stubborn, and you can't get to the delicious fruit inside. Then you realize it's not curved into a smile. It's upside down, a frown. A frown because that's what you're left with when the stem doesn't crack and the top bends over and the fruit you thought you wanted at first becomes a mushy mess of disappointment. That's what a banana does, it disappoints.

And then the yellow begins to dim as your eyes are drawn to a subtler gleam, the gleam of an apple, hypnotizing you like a snake charmer. Vibrant colors, various sizes, craved tastes. An apple also has an outer layer, but it's much easier to penetrate, chipping away at the tender flesh searching for that fulfilling core. They even say "the apple of my eye" because an apple doesn't make you feel like an option; it makes you feel like a priority. Even Snow White couldn't resist taking a bite of the tantalizing fruit.

This is an apple, and that is a banana, and of course I know which one I want.

"Evie?"

The hypnotic sound of this familiar voice was like glass hitting a hardwood floor. Of course I knew right away who it was, and I tried not to sweat when our eyes met.

"Luke? I didn't know you shopped here." My knuckles whitened as my grip tightened on the cart handle to keep myself from swaying toward him.

"I don't usually, just thought I'd pop in and see if there was anything I liked. Hey, you never returned my call."

I saw a gleam again and thought it was another apple, but when I looked down it was just light reflecting off the ring on his left hand, blinding me for just a moment.

"I know. I'm sorry Luke, but the answer is no."

"All right. Well, I guess I'll just see you around then."

I wondered if he could feel my increasing heart rate as he leaned in and picked out his produce.

"Yeah, sure."

As he walked away, I knew exactly which one I wanted. I knew like I always know every time I come to this same grocery store. But then I look over and see my smiling husband, Adam, turn the corner, and I choose the banana instead, just like I always do.

LUKE

Like a good husband, I go pick out some fruit at the store even though it's one I've never been to. Mari says she wants the kids to eat something healthier than French fries and Oreos. She's been asking me for days, which has to be the reason for her scratchy throat. Come to think about it, she's been wanting me to run so many errands it feels like I'm rarely home these days. I need to be a better husband.

While I'm at it, I can pick up some anti-itch ointment for the irritating rash on my hand. I don't even know how I got the stupid thing, but it's spreading. Actually, I've been battling symptoms of eczema for the passed five years, randomly breaking out in apple red patches of tender skin. I know scratching will only make it worse, but it's so hard to resist the temptation.

I find the cream first and then walk over to the stand of bananas where I run into a perfume I've smelled a million times.

"Evie?" She looked up at me in the same way she does at church every Sunday.

"Luke! I didn't know you shopped here."

"I don't usually, just thought I'd pop in and see if there was anything I liked. Hey, you never returned my call." As the pastor, I make it my priority to personally call members of the congregation and ask for Sunday morning volunteers, but it's always difficult getting Evie to say yes. She lowers her head for a moment, and I can tell she caught a glimpse of the unpleasant redness developing on my fingers.

"I know. I'm sorry Luke, but the answer is no."

Is it really that disturbing? I'm sure it's not contagious or anything. That's why people make me laugh; they always assume the worst of everything. But, I suddenly start to feel a pulsating sting on my knuckles as I grab a few apples, almost like a racing heartbeat. I think this is going to be the toughest break out yet. It was probably best that we not stay and chat.

"All right. I guess I'll just see you around then."

"Yeah, sure."

I carry the bag with my untainted right hand and leave her to her shopping. But as I walk away, I can no longer withstand the urge to scratch my hand, the part of my hand concealed by my wedding band. I take the ring off, slip it into my pocket, and lightly scratch. Already it feels better.

ADAM

He was in the refrigerator section. The simple task of picking out yogurt had become climbing a mountain in a blizzard. There were way too many flavors, too many options that made it almost impossible to choose just one. But then again why should there be just one? There was peach, blueberry, lime, strawberry, banana, strawberry banana, apple, and possibly ten more, all of them refreshing and delicious. And on top of all the flavors, there were also countless brands. Brands that deserved the chance to prove why they were better than the others.

Staring at three shelves of fruity yogurt made him think about all of life's options. The luxury that humans had to choose their food, clothes, haircuts, stuff like that. Hell, plastic surgery even allowed people to choose how they looked. There were so many availabilities in the world, so many opportunities, that it was impossible to be unsatisfied. That was the beauty of options; they kept people content.

It made him happy to know that he could wear a pair of slacks to dinner one night and a pair of ripped jeans the next. He could take his car to work or he could ride his bike. He could get buzzed off Coors light or blackout from shots of yeager. Not like that sober Luke Damon from church who gels his hair every morning and wears the same goddamn suit from Men's Warehouse. Nope, not Adam. He knew that variety mattered, and that if a guy didn't change it up every once in a while his life could become a mushy mess of disappointment.

He felt his phone vibrate in his pocket. Variety matters.

"Hello?"

"Hello Adam, it's Marilyn."

He could hear her candy apple red lipstick through the phone. His left eyebrow arched as he glanced over both his shoulders.

"Oh, I didn't expect you to call so soon," he said so only the yogurt could hear him.

"Well I had such a good time, I thought why wait?"

He smirked to himself. Her scratchy voice reminded him of their late and loud night together.

"I like the way you think."

"So when can I see you again?"

"Soon. Very soon."

He didn't wait for a response before he hung up. He grabbed a yogurt of every flavor and, smiling, turned the corner to meet his wife, Evie. Oh the beauty of options, he thought to himself.

Isla Muneca

Jamie Farthing

"That island was just too tempting a place for three young girls looking for adventure. But when one lost her footing, the weed-choked river claimed her for its own. You see, there was this man who had it in his mind to live on that very island. He was one of those types that had nobody looking out for him, nobody carin' if he lived or died." The old man's fingers, twisted from years of hard labor, gripped a non-filtered cigarette. "His first night, he saw that poor young girl's spirit wandering around lost–angry at what's happened to her. To appease the spirit, he built an altar of what every little girl wants...dolls, offerings he hoped that would keep the spirit from bringing harm upon himself and this very town. Every year, on the anniversary of her death, we bring more dolls. Cuz' you must always leave an offering. Lest you find yourself in the river."

The boat–more like a raft that had been constructed with Popsicle sticks fashioned by kindergartners on a paste high–bumped into an even worse dock. One look at the island, affectionately called Isla De Las Munecas by the locals, and I wished we were back in our suites in Mexico City. I had done the appropriate research, dug into local legend, spoke with the impoverished people who would be more inclined to believe and looked great on camera, and I did it all with a damn smile on my face.

There was a time, when I first became a part of the show, when I shared in the naivety that I would one day be a part of a monumental discovery. An aspiring parapsychologist, I was ecstatic to become the field producer of Truth or Myth, a cable network show that sent a team to investigate paranormal legends around the world. After the six years we've been on air, I firmly believed that the show should drop "Truth" from its title.

"I can't wait to get this one started." Erica actually skipped past me, her golden curls bouncing in tune with each perky step.

"Don't get your hopes too high," I call after her, checking my cell's reception. Nothing. Not one fucking bar. "God, it stinks out here."

Undeterred by my skepticism, Erica jutted her arms out into the stagnate, humid air. "I think it might be different this time. I mean, come on! Look at this place!" She stood, running her hands over decaying dolls near a rundown shack that looked ready to topple at just a slight suggestion of wind. Or one more doll. I thought, feeling my shoes sink into the mud. Doll Island couldn't have been more appropriately named. Tiny bodies hung from the trees, were tethered to the surrounding bushes, and even nailed to every available inch of the shack. Barbies hung from the door jams, and handmade cloth babies were lashed haphazardly to the roof, their broken button eyes staring up to the cloudless sky. Mold grew in the empty eye sockets, others had their tiny eyes sunken inside their plastic heads but were missing a body, and I thought I saw a small snake winding its way through the armless torso of a forgotten Feed Me Katie doll. The bright, wide-eyed stare of a few new additions not yet stained with the evils of the elements seemed to follow me as I called out to the crew.

"All right, the sun is going to set in fifteen." I kicked at a hairless Barbie that had somehow gotten under my shoe. "Scott, get some B-role, Erica start rolling sound, and where the hell is Jackie?" He motioned to the dock where Truth or Myth's host and constant pain in my ass, Jackie, stood with her arms across her chest.

"You gotta leave an offering to the girl," she said, parroting the old coot a little too well for a girl with a voice that was three octaves higher than necessary. "Or they'll get ya."

"Well, isn't that what we're here to find out?" I asked, pushing aside a doll painted like a clown that dangled from a branch in front of me. I shivered. I hated clowns.

"You don't want to hear the scratchin'," she continued, her heavily made-up eyes darting around the small island. "If you hear that, then it's too late."

"When has anything ever happened on these trips? Don't get superstitious on me now." The putrid river swallowed the sun, stealing the last of the light. Our boat knocked against the ageing dock, lending a sort of percussion to the ear-buzzing music of the insects searching for food. "Come on Jackie, it's time. Scott, start rolling."

We gathered around Jackie, the camera's lights reflecting off her iridescent blue eye shadow. "Doll Island," She began, "Truth or Myth?" She had barely finished the sentence when the camera's lights burned out. I sighed, turning to Erica who motioned to her earphones with a shake of her head. No sound.

Jackie's voice cracked in the darkness. "We should have left an offering."

"Don't be so fucking dense." I turned to head back to the raft with the hope of finding a flashlight, when I heard it.

Scratching. Like thousands of tiny plastic hands reaching out from the inky blackness. I fell to the muddy ground, the sounds of my crew's screams mingled with my own.

Sacrament of Penance

Ashley Fisher

Laura climbs into the old hatch back Camry and settles into the familiar smell of cigarettes and tea tree oil. She places her feet on the edge of a cracked leather seat and picks at the goose bumps on her knobby knees, her legs are covered in blue and brown splotchy bruises.

"I haven't shaved in like three weeks. So sexy." She stretches the fabric of her perfectly faded black rayon dress around her legs to her ankles, hugging her body in close.

The air is thick with smoke that fills the car and makes her eyes water and burn before it escapes through a crack in the sunroof, the only thing that still works in the car.

"My counselor says the environment we create is a projection of how we feel inside," says Laura staring at the pile of cigarette butts, fast food bags, and moldy coffee mugs which had collected where her feet should be.

Ethan sits next to her and rolls his eyes, dialing a number on the taped up old Blackberry he'd managed to keep working for three years. She waits with him as each ring brings dread: a faint bleep, an unreturned message, waiting, more calls.

Finally there's an answer. "Hey, are you open?" Ethan asks.

He pats his pockets. His face shows no expression, she bites her thumbnail, eyes held wide, seeking answers. He pulls out an ID, an old BART ticket, and some soggy, crumpled dollar bills. Why keep the ticket? No use for it now.

"Um, a half...ya...okay," says Ethan before pressing end.

"What did he say?" Laura asks.

"We're meeting him in thirty."

"So an hour?" she mumbles with her lips pressed against cloth covered knees.

Truly it doesn't matter where or when, but the possibility is enough to lift some weight off her heavy chest and release tension accumulating in her joints. She pulls her tangled black hair onto one side and cracks her neck. She twists her torso to crack her spine and face the back seat. The trash in back was once high heaven in idle times. Today nothing but a few chocolate Clif bar wrappers and a corked bottle of Trader Joe's two buck Chuck on soiled floor mats.

"Are those the same bottles from the last time we hung out?" she asks.

"I dunno, maybe." He turns the steering wheel to exit her neighborhood.

"That was like a month and a half ago, you could get so fucked for an open container. You crazy boy!"

"No way! Cops love me, I just look so sweet and innocent," brags Ethan.

This statement once was true. But his skin has grown green and pale. His smile forced, his voice muffled, and his eyes vacant. Laura doesn't have the heart to tell him, but no longer has the appearance of a naïve teenager. The transformation is made more apparent with the time they had spent apart.

Uncomfortable sweat grows between bends and joints from the useless air conditioner and stagnant summer day. Laura's cheek is pressed against the glass. The coolness of the window makes a wonderful contrast to the sweltering heat. Everything is sticky, and the scent of hot wet asphalt fills the air from some unknown source. Nausea, weakness, restless legs familiar sickness. Really, Psychosomatic withdrawal?

"You know what? The mind is just a crazy bag of tricks, don't you think?" Laura looks at Ethan, a contemplative expression in her fawn like, chestnut brown eyes.

"You're ridiculous... Remember how you said you would never admit you were hooked till' you were certain you were dope sick and not just like, sick sick?"

"Yeah."

"Well, I'm dope sick; I'm sure of it, don't make me think," he says. He could always find humor in morbidity, a fine method of defense.

There it is, the usual Jack in the Box. Ethan pulls around back near the drive through entrance. Being around lunchtime, cars are lined up, attracting attention away from the loitering car. The invasive sun stings the exposed skin on Laura's face, neck, shoulders and chest.

"How anyone honestly enjoys tanning at the beach is so beyond me. This is a form of torture"

She pulls down the visor to hide from the day, catching her reflection in the magnified mirror. Closely, she examines each pour for tiny toxic pockets. A few unacceptable blemishes vandalize her doughy cheeks. When in God's name did this this happen? Yet another reason to thirst for the upcoming escape was added to the list.

It's usually forty for a half, unless prices changed during the time she was in treatment. She tosses a clammy ten dollar bill onto Ethan's lap. Her mother gave it to her to buy food for the day. What a pitiful women, ignoring the obvious signs. The charismatic, bullshit rant this morning. Why life was just so much better lived on the straight and narrow, how she was miraculously cured. Laura knew exactly what that money would go to the moment it entered her hand. Everything had shifted, no eye contact, tunnel vision, the one track mind took hold.

"My mom is so fucking blind, how is she still giving me money?" says Laura, chin held high, brash smile across her face. Fuck Why do I even say stuff like that? I'm a useless human, a worthless wreck. I've ruined her life...But she ruined mine first.

Ethan giggles. He never had a mother; he could care less for maternal compassion.

Ethan lines the bills in a neat little rectangle and folds them over in preparation. He doesn't have much regard for money. He never mentions how he managed to buy a few grams of black a week. He doesn't rip anyone off as a middle man; he doesn't steal from people he knows. He's never distrustful, except the year he spent working at the American Apparel downtown. He must have stolen over ten thousand dollars' worth of merchandise before he got fired, most of it for Laura.

He does most everything to have her near, and she's fascinated by his soft boyish demeanor. The way he walks in small timid footsteps, often tripping over his own feet. How he's always tugging at his hair and yawning as a nervous social tick.

"I just feel like a lost little boy, begging for someone to hold me," he had once said, though she already knew. He's her ragdoll, her novelty plaything.

Laura grabs him by the hair. It's thick with grease. She pulls his head near, planting a kissing on top of his head. For a moment, this fills a gaping hole. She closes her eyes, the side of his face caressed into her flat chest; she nuzzles into his scalp and breathes in deep until it hurts. More filth, the never-ending scent. Guess it's true, scent is the strongest sense tied to memory.

Neglected hinges sound like nails on a chalkboard from the back right door. Laura releases her arms, jolting back to face forward. Patrons in red and white seats feed pudgy children fries glazed in ketchup through dust filmed glass. A middle aged women gets up, trash in hand, leaving three elementary school aged children at the table.

"Cuarenta," says the faceless man.

The little boy smacks the girl; she begins to cry, the mother returns to yell at the third boy who hasn't yet looked up from an iPhone. We're all destined to be miserable.

Ethan reaches back to become obliged and fingers meet in exchange. The door opens once more and quickly slams shut. Held deep in his lap, Ethan rolls the commodity around on his finger tips.

"Nice, he hooked it up."

A miniscule red rubber fragment enters her palm. It's placed cautiously inside her bra; the unspoken routine. He turns the keys in the ignition, the car falters before starting. Laura clatters together heels and toes of her soiled white Keds, pretending they are ruby slippers as they sail away.

"There's no place like home, there's no place like home," she repeats being campy as can be. Ethan knows exactly what she means.

Laura turns the grey paint chipped knob to Charlie's downstairs studio apartment, Ethan follows behind her. The room, roughly ten by twelve, reeks of body odor. The only window is covered by a toy story quilt. The light is limited to a wrought iron table lamp, without a shade, on the floor in the middle of the room. Sprawled out on disgusting beige carpet are four humans, resembling a syndicate of ghosts.

"Hellooo," says Laura in a whisper, waving her hand.

"What's up?" says Charles, propped against a stripped twinsized mattress. He takes his pin-point pupils off his laptop and points his thumb to a thick, rough looking Asian girl sitting next to him. "This is my girlfriend Tanya. You guys met?"

"Hi," says Laura.

Tanya circles her thumb around the center of an iPod, headphones in, unaware. Chitchat is bullshit anyway. No one cares who lives or dies. Sharing always lacks courteous intentions. Favors are only granted so that in times of drought they'll be returned. Six people in a room soon to be dissociated on hands, knees, or blown out shoes, when not fixated on their own personal sludge.

The room closes in, a lion's den. In the corner a duo nod off, dead weight onto each other's bodies. His head rests on her shoulder, lids sealed, gross gaping mouths, raising only his eye brows to signify his dreams. She has lacerations on her chest, from hours of scratching at her itchy skin. A nipple hangs out of her black tank top. No one notices, no one cares.

Shit! What am I doing!? Throwing forty two days down the drain. I mean, that's not much but it's a start. No longer did Laura stay up, screaming in the night while her feet kicked hard against a mattress. No more day time shivers, or the never ending flu. That weathered feeling hidden deep her bones or the melancholia. And though shame never left, it was no longer as suffocating as it once was.

The likelihood of contracting Hepatitis is incredibly high if she sets out for another run; nearly everyone she knows has it aside from her and Ethan. They only share with each other, so he says. I probably already have it; I placed my future in a junkie's word. It's hopeless. Might as well give in and give up. Never be worthy of living, and why die when you can have brief moments of oblivion.

This is only supposed to be a phase. Marriage, children, family, but the path towards that happy ending gets put off month after month. Now every last part of her could be tainted, down to her blood. Purity would be unattainable. An irreversible fate. Who would love her, who would hold her?

It would take all the strength in the world to turn around, exit the room, and escape from her own self destruction. But she's infinitely tired. Just this one last time and only a little bit.

It's too late to turn back. Laura walks over to face Ethan in a corner, knees nearly touching. She feels between lace and skin, pulling out the prized possession, she hands it over. It's mostly his, so he goes first. Still won't give me his hook, so he knows I still need him. Asshole.

Ethan pulls a weathered black pencil holder from his green canvas backpack. Out of that he grabs a stainless steel knife, syringe, and the overused spoon he'd grown so attached to, lining them up on stained carpet between their pretzeled limbs.

He hunches over, bones protruding from his back. He opens the serrated pocket knife and slits the red rubber seal to unveil the dismal brown dope. It looks like heaven and smells like vinegar.

"Did you put enough for both of us? I don't need much at all, cause I haven't done it in a while."

"Ya...Charles, lemme get some water," says Ethan

Charles doesn't care to look up, just totters his head a few times over the spoon and his instruments. When he's done, he pulls out a white lighter.

"Those are bad luck you know," says Laura.

Ethan ignores her and holds the stem of that mutilated spoon. He flicks the lighter.

Vapors of that sour, soiled stench hold memories of small dark places and uncontrollable vomiting. Laura's abdomen tenses with defiled nausea. She holds her hand over her face, and her mouth begins to salivate. For such an omen to a treat it's like a punch in the stomach to think that smell used to do nothing for me. Now it is everything I beg for and can't bear to recall, all in one.

Laura bounces her knees up and down as she cracks her knuckles. She shivers. A chill, fevered and impatient, crawls from her shoulder blades to the root of her skull. Ethan sucks up the murky liquid through soggy cotton, and then places the syringe between his teeth.

Without looking down he undoes his belt and whips it off. Buckles of metallic clang to tighten as he teethes the leather and inspects his arm with ingenuity.

There is a beauty in habitual self-destruction once it becomes an inherent routine. An all knowing, cosmic, killing action. Laura's eyes became distant, her mind lost. She watches him poke and prod at his flesh with blaring jealousy. Lines of blood run down his arm onto his shoes in attempts to hit. His veins had collapsed, miss after miss. Yet to Laura this is natural. I understand, I comprehend, and it's unstoppable. But hurry up.

"Fuck, finally." Ethan loosens the belt removes the needle, placing the cap back on. The lump in Laura's throat restricts her breath. She flicks off the orange cap in a frenzy to begin. Careful not to dull the refined point, she sucks up what's left of the tainted pool and slides the belt around her arm with cryptic welts, not yet healed, before placing the end under her shoe. Zeroed in and silent with skill she scouts for greens and blues through the muscles that emerge. Her hand is scarlet then royal shades of purple, nothing but Laura and her "profession".

She finds a winner along the side of her wrist and in it goes, pressing upward with her bloodstream. It hadn't been that easy in years, a hiatus wasn't so bad. Pulling back, a ruby color drifts in like a lyrical dance of soft fabrics. She pauses to admire for this is the threshold. So sickly accomplished, she smiles to herself, then pushes to release. Waiting for liquid gold as it starts in the heart.

Suddenly she is soiled from head to toe in grimy bliss, covered in a warm blanket of degrade and filth. Lids willingly slump and discernable eyes leave plain sight to enter a glorious utopian world where reds and browns kaleidoscope around labyrinth-like justifications. Her neck is calm and her skin is still. Breathing reinstates, she looks up at the strangers she had recently despised as if in annoyance, "It's all happening!" They are still enchanted by their pious worship.

"That's better. Well worth the wait...How about a song?" she mutters to herself.

Really, any song would do at a time like this. The possibilities are endless. Nothing could hurt me now.

Truth or Consequences

Sean Frede

The little border town where this here story is set isn't called Hot Springs anymore. No, no one's called it that since, must have been, 1950. Back then NBC had a quiz show hosted by Ralph Edwards called Truth or Consequences. Old Ralph announced the show would air from the first town that changed their name to the name of the show. Hence, "Hot Springs" became "Truth or Consequences." It's the type of town that people drive through and soon forget. Vacationers dreaming of Albuqerque or the Four Corners only to leave behind trails of dust that get caught in the local's throats.

The town lies along Jornada del Muerto. It's simple desert basin given its name by Spanish conquistadors along with the hundred mile trail that runs through it. Route of the Dead Man. The trail is bordered with the green skeletons of Joshua Trees, once flourishing with vibrant flowers, now barren totems standing erect praying for rain.

This little ole town has a past like all the others, a secret. Back in forty-five the government sent letters to any New Mexico towns that bordered government land within fifty miles. They stated that no harmful side effects would be brought on by the Trinity Testings. No harmful side effects.

The swings in the park sit alone, the creak of their chains rattle in the wind like the bones of coyotes hung from the necks of ancient Indians. T or C high sits boarded up along with Indian Hills Elementary. Laughter is rarely heard. It only escapes the lone bar, The Barn Owl.

Not a single child has been born in thirty years. Not a one.

Just another dry sunny desert day as Gus Laramie walks down the same scuffed sidewalk along Main Street like every other day. This town's got her townfolk like any other and this here's one of 'em. His saddle bag filled to the brim with magazines, bills, letters from other states, bouncing in between his hips. The same bag that held those government letters that his grandfather dealt out to the citizens.

He tips his hat to everyone that passes by and steps off the sidewalk for the ladies to pass. Good ole Gus. He has a slight limp in his walk because his left leg is a bit shorter. In high school, he was "Left Leg Laramie." Eventually "Lefty" stuck. The kids were cruel back then. Now they've grown up. Gotten worse, like a lot of things.

"Eh there, Left. Hot enough for yah?" Gary, the owner of the Barn Owl says. He models in front of the green door, paint peeling and chipping. Every town has got a bar keep, the one that knows all the secrets of the townfolk, a regular reporter. Who would have thought that ole Gary has a bigger secret than all of 'em.

"They say it's going to be hotter next week, just you wait."

"Ain't that a bitch." Gary opens the door. A faint red glows all around, no sunlight reaches inside.

There's no music playing. The only sound is the hiss from the barn owl in the black cage in the corner. Gus stares at her eyes while holding onto the brass rail along the bar. Her head moves in figure eights while wings flap the air, her beak pecking at the bars. All the barn owls left T or C after the government testing's. Gary was able to get his hands on one from a back alley deal. He claims he caught it with some bait and a burlap sack, never letting it see the light a day. A real shame.

Gus notices the worn down peg the owl is standing on. Wood that once knew sunlight and growth now slowly gets worn down from pacing talons, year after year has turned it into a toothpick. Soon it will just disappear. Gone the way of most things.

"Shut your trap, Shirley!" He throws some peanuts at the cage.

"How many times do I need to ask, change the name of that damn bird, Gary."

"I do it to kid. Besides, that's all old news, mail man. What do yah got for me?"

"Just a few bills." Gary snatches the letters from Gus's hand.

"Always the bearer of bad news, eh?" Gary pokes Gus in the ribs and lets out a chuckle. He's a big man, tallest in town at six foot five and bald. Claims he's always having to beat the women away with sticks.

Gus remembers when Gary would shout, "Shoulder check!" in the hallway in high school and slam Gus against a locker making him drop all his books. "Easy there, butter fingers!" He would say every time as the boys and girls would laugh as he bent over to pick them up.

"Well, this route won't deliver itself," Gus quickly turns on his heels and walks out into the sunlight. Gary stands at the door watching Gus hobble down the road towards the rising sun.

Gus feels that same sun beginning to burn as he moves on, adjusting the strap on his pack. Following the passed down route his father and grandfather travelled every day. It is up to him to deliver to the people of Truth or Consequences. Up to him to decide if he will plod on this same path. The ground being worn down like that damn peg that owl paces on.

Every morning is the same for ole Gus. He turns off his alarm, brews coffee and heats up his oatmeal. After he gets the shower going he opens his medicine cabinet, the faded picture of the brunette with librarian glasses smiling back. He runs his finger along the edges of the picture. He closes the cabinet and stares at his pale and bony frame, lifting up his stomach and letting it drop and bounce, then pats it. He stands and wonders what he could have done more of to keep a hold of her. Gus has been wandering for quite some time now. The answer sure isn't going to pop out of thin air.

He keeps walking on the trail. Gus was and still is a smart boy, but what happens when you squeeze a hose too tight? Nothing comes out but a few drips. Not even enough to quench a thirst.

Gus walks past shops left and right and comes to a stop in front of the travel agency. The A is missing in travel and it hasn't been opened in years. Ever since children stopped being born people became afraid to leave. The outside world caused this problem, not them. They found comfort in keeping their feet stuck to this cracked and barren land. The same land where cacti struggle to survive. Funny in one of those dark ways.

He looks into the agency shop and sees the same ad of a broad shouldered man leaning against a palm tree in front of the ocean. Three women tan lazily. Gus closes his eyes and runs his hand along the dusty glass, leaving behind lines. He pictures himself in the poster. He can smell the salt filled air. The waves crash and recede against rocks. The briney taste of oysters envelope his mouth. Before he can get lost the ghostly howls scatter his face with sand, back to reality. His bag is half empty now as he moves on, bent over. He follows the sidewalk. His path is safe. It starts and ends with his home. Gus never has to worry about veering too far off. I always wonder if that's comforting or bothersome.

The sidewalk ends and he begins the rest of the route on the dirt path that leads to the houses. His feet get stuck in the rut, slowly getting deeper and deeper each day. No plants thrive from beneath it, nothing but dirt and clay. It's the same route he has always followed and is the same route his grandfather began. Gus looks down and notices the cracked clay breaking beneath his feet.

Gus reaches the neighborhoods of Adobe houses, all with tan rock lawns. The tan houses mingle with the lawns, it's impossible to tell where one ends and one begins. A wooden sign hangs from the wrought iron gate. The sign is painted in black letters: YARD SALE.

Betty sits on her red, white and blue lawn chair filling in a crossword with any damn word that'll fit. She never bothers with the questions. Just taps the pencil on her cheek hoping one day she'll find the word she's always been looking for. The one that fits just right.

Some wife mingles through a box of children's clothing. She picks out a shirt with Strawberry Shortcake on the front. Moths have eaten holes in it. She will buy it and take this shirt home where her and her husband will wake up before sunrise and set it out along with other wares on their driveway. It will sit on a green foldout table with more children's clothing and toys. Families will come and buy these items, take them home and do the same. They buy and sell to keep memories at bay. These are the consequences brought on by people trying to escape the truth. This is what Gus must realize.

"Afternoon, Bets. Another yard sale I see?"

Betty puts both hands on the arm rests to get up from her chair. Her cut off sweats are wet and her shirt is half unbuttoned revealing saggy cleavage as she leans across a rusted table set with three glasses and a pitcher of lemonade and begins to pour Gus a glass.

"Hiya Gus, any news from the outside world?" She asks this almost every day, deep down hoping for some far off letter that is accidentally mailed to her. News of some other place than here. It is her dark obsession.

"It just seems Benigan's department store is having another sale. Got a catalog for you." He places it on the table next to the old Army ammo box that holds five dollars and twenty-six cents from the day's profits.

"Their clothes are so tacky, throw it out."

Condensation begins dripping from the glass he holds, his fingers leaving wet trails that know no bounds, moving from one place to another freely. He quickly wipes his hands dry.

"I hear its gunna be even hotter tomorrow," as Betty fans her face with the department store catalog. She rolls it in her hands and swats a fly dead on the table.

"Ain't that the truth, mind if I look around?"

"Be my guest."

He quickly scans the toys and clothing and goes to a box full of books and opens up one about America's National Parks, published in the 1950s. Steam rises from pools of yellow, green and aqua in Yellowstone. Cars drive through giant, looming sequoias. Hikers stand on top of Half Dome, dwarfed by magnitude. He puts his face closer to the book and can smell the earthy worn pages, like wet dirt after a thunderstorm. He can't help but notice the trails in the pictures. The trails that start in one place and end somewhere else. He has spent all his life on a trail but not like the ones in the book. These trails offer a destination far from where you start.

"How much for the books, Bets?"

"You can just have it, Hun."

"You're too good to me, you know that?" He puts down the glass of lemonade as Betty swats at another fly but misses this time. They both stop and watch it fly higher and higher until the gaze of the sun burns their eyes and the fly is lost forever.

"Well I should be getting on, more news to be delivered."

"You take it easy, Darlin'." She grabs both arm rests and lets out a groan as her knees creak back into position against the worn out lawn chair, the stitching frayed and falling apart.

Gus takes the book and puts it in his bag, almost empty now, just a few more letters and a couple of magazines and the day is through. The trail gets shorter and shorter as the day wears on. He can see the end of it, the point where he stops and turns around only to start it up all over again the next day.

He starts to think of the last fight with Shirley, when he finally couldn't keep a hold of her. She kept talking about wanting to make it to the Grand Canyon but he kept using work as an excuse to back out of it. He claimed the basin they lived in was just as beautiful, all they had to do was take a thirty minute drive and camp out for days. They wouldn't have a worry in the world and be safe, being that close to home and all.

"Yes, that would be a nice, safe trip. Wouldn't it?" Whenever they argued she would never look at him, just stare at the same Norman Rockwell on the wall. That one called "Going and Coming." He always remembered the boy with his face out the window staring forward with the dog, both feeling the wind against their faces as they drove along the highway, no end in sight.

"I just can't take that long of a trip, this route won't deliver itself."

"Then get someone to cover for you. All they have to do is walk in a damn circle and drop off letters."

"This weekend we will go to the edge of the basin where the sun always seems bigger, the same spot that we always go camping at. We will have a great time, Honey."

"Don't you get it? I want to go places, see places. I'm tired of the same damn thing. We've never had to worry here. I need something that gets me worried. I need something new. Damn all your precious packages for a week. These people can wait. I want something new."

After that fight she took the Rockwell off the wall for good. He still didn't understand what she meant about needing something new when everything she needed to survive was in this town until now. But he's starting to.

Gus stands under the awning with his book open staring at all the Adobe houses, at all the cracked vacant nesting boxes. He looks down at the book again while licking his upper lip, that little duck churning against the water in circles. He thinks of the last words she said to him and sees the trail that leads to Crater Lake and understands. He sees the trail beneath his feet breaking apart. The trail that leads nowhere.

Behind him the clouds that should have burned off move closer. They have become darker and the ghosts of the Indians along the basin howl their forgotten cries pushing the clouds in closer and faster. Eating up the sky above. He looks into his bag of deliveries. One left.

The address is for the Barn Owl and has Gary's name on it. He won't hear the end of this, he thinks. Gary was always getting letters and packages from all over. People began even calling him the ambassador of T or C. Gary took this as a complete compliment and ran with it. Gus has always had to deliver these packages and it seems like each week he gets something new but always sees him with the same old stuff.