The true story of the Bridge on the River Kwai

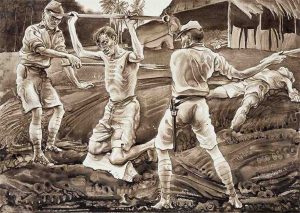

The Japanese guards were brutal and merciless in punishing the POWs for not obeying their commands.

“Oh, please! God please! Just stop! No more! No more! Please don’t hit me anymore!” pleaded John, a private from the Australian army. Covering his face with his battered arms, John, a POW under the Japanese command, was down on his knees begging for mercy and pleading to the Japanese guard to stop beating him with his bamboo stick. Every time the guard struck his face, neck or back with the bamboo stick, he cringed in pain. His lacerated and weak body due to the beatings and his illness caused him to drop on his knees and go into a child pose like in yoga as he uttered in a weakening voice, “Please, guard. No more! Please don’t hit me anymore! Please! No more!” Hunched over like a baby crawling on his knees, John was bleeding so badly from the back, neck, and arms. Blood was trickling down his arms from his back and neck. His face was no longer recognizable showing bamboo marks on both sides of his face and forehead.

The POWs feared the Japanese guards. They dared not disobey or challenge any orders given by them by the guards.

John was totally helpless and hopeless. He was clinging on to life. Looking at John helplessly, the other POWs near him could do nothing. It was hard for them to continue working on the railway forced on them by their Japanese captors. They were frozen and quite fearful of their own fate as well. They could only stand at their positions and stare at John. John represented what could happen to them if they disobeyed, looked at the guards the wrong way, defied them, stopped working or just gave up working from exhaustion and weakness. All the POWs coward from the brutal Japanese guards. They feared them so badly that they dared not to offend them in any way. To prevent it from happening, they did their best to keep their arms and legs moving to show they were working on the railway despite their tired and weak bodies. The brutal and fearless Japanese guards, however, had no reservations of beating or striking the prisoners whenever they wish if the POWs talked back, looked at them the wrong way, or just stop working due to exhaustion and weakness. The bamboo stick, found everywhere in the jungles of Thailand, was the guards’ favorite punishment tool. It was strong, effective, and damaging. The POWs faced a life of doom and certain death.

“Please! No more! Please stop! Oh God stop! I can’t take it anymore. Just let me die here,” begged John. These were perhaps his dying words. Yet the guard was merciless. He didn’t care. He seemed to enjoy beating John more as he was crawling on the ground like a baby. John was suffering from dysentery. Like all the other POWs, he was over overworked, exhausted and sick. He was physically and mentally drained. His body and mind had given up. He had no more energy. He had already collapsed and lost consciousness. Yet the Japanese guard kept beating him harder to force him to work. The POWs could do nothing to stop the brutality of the Japanese guards. They understood them to be merciless and inhuman people who used their brutality to get things accomplished. To the Japanese, brutality was a means to efficiency and purpose. The POWs were the means from which they would achieve their goal – to build a railway from Thailand to Burma. They bathed in their glory for their superiority over the vanquished. During World War II they seemed unstoppable. At the POW camp the prisoners unwilling came to understand the Japanese brutality and mentality. But they absolutely had no respect for them and their cruel ways. They knew they were at their mercy. Their only option was to obey and do their work. Their survival depended on how long their bodies could continue working facing the adversaries of Japanese brutality, jungle sickness, malnutrition, lack of medical care, unhealthy living conditions, and exhaustion. Thousands had already died, and John could be the next. The POWs understood their fate and there was nothing they could do about it. This was the miserable life of the POWs who became human slaves to the Japanese building the railway system from Thailand to Burma during World War II.

Cruel, unjust, and inhuman events in history have happened all over the world. Such events like the 9/11 World Trade Bombing in New York, the Holocaust in Germany, the atrocities committed by Khmer Rouge regime led by Pol Pot in Cambodia, and the Bataan Death March in the Philippines need to be remembered, analyzed, understood, and scrutinized so that human civilization will learn from it and keep it from ever happening again else uncivilized, unhinged, and unchallenged countries will repeat them and cause more deaths to the helpless in the world. One such event occurred in World War II during the building of the railway from Thailand to Burma involving 250,000 Asian laborers and 75,000 Australian, British, Dutch and American POWs. This event has been memorialized in the 1957 movie called “The Bridge on the River Kwai.” The real history, though, of how the railway between Burma and China was built, including the bridge, is a horrific one. Here is their story.

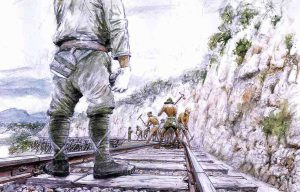

Romushas, or local workers, were paid very little but helped the Japanese to complete the railroad lines.

Before the outbreak of World War II, Japan invaded French Indochinaand occupied Manchuria, Taiwan and Korea. – In December 1941 the Pacific War began with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and the invasion of Malaysia. By mid-1942, Japanese forces were fighting the British in Burma, their ultimate aim being an offensive against India. Because the Japanese had to maintain their armies in Burma, they needed a more secure supply route than the vulnerable sea-lanes between Singapore and Rangoon. Thus, they decided to construct a railway, 415 kilometers long, through jungle and mountain from Ban Pong in Thailand to Thanbyuzayat in Burma. This railway, which crossed over the river Kwai, would be used to carry their supplies as a vital link for the Japanese forces in the war. Since the Japanese had free labor through the captured Allied POWs and the local workers (or Romusha), they were able to build the railway and the bridge to connect Thailand and Burma. With a multi-national workforce of approximately 250,000 Asian laborers or Romushas and over 60,000 Australian, British, Dutch as well as over 15,000 American POWs (prisoners of war), the Japanese could construct the bridge as a supply rout from Thailand to Burma where they were expanding their war efforts. Work on the line began in southern Burma and in Thailand in October 1942. On 16 October 1943, the two ends of the Burma-Thailand railway were joined at Konkoita in Thailand. Within 16 months the bridge was completed but it took another two years to complete the entire rail line. Instead of the five year predicted completion, the bridge on river Kwai, was completed in 16 months. How was this possible?

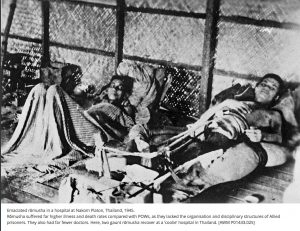

Romusha workers suffered more than the POWs as they had no organization and no medical care unlike the POWs.

During WWII, the Japanese set up a POW camp in Indochina on an island on the banks of the Kwai River. Since they had these POW camp in Indochina, it gave them the inevitable advantage of using the labor of the POWs and the locals to construct a railway bridge over the river. During the time of construction from 1942 until its completion and maintenance in 1945, the Japanese commanders and guards were ruthless and merciless to the prisoners who were beaten and tortured. If the prisoners or romusha resisted, refused to work or disobeyed the guards, they were severely beaten by the Japanese guards. Not only were the beatings an obstacle for the POWs, but also their exposure to harsh conditions of the jungle, the rain, the sun, and the snakes. There was a third devastating factor that caused the demise of the POWs and Romulas. The unhealthy living conditions, their meager diet, diseases from dysentery, malaria, cholera, beriberi, and pure exhaustion caused the deaths of thousands of POWs and Romulas.

The Japanese had a hierarchical system of discipline in which physical punishment of lower ranked soldiers were common. If the POW were a high ranking soldiers or officers, the Japanese guards would give him more leniency and attention. However, if a prisoner of war were of the lowest ranks, then the Japanese guards were at liberty to punish them as they wish and often brutally with a bamboo stick, their favorite punishment tool. On the railway, Japanese engineers exercised the most power. Beneath them were guards, mostly Koreans, who became renowned for their brutal, often murderous treatment of prisoners of war and the Romusha.

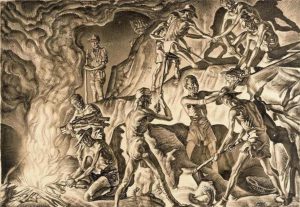

The railroad work went on 24 hours a day with the aid of oil pot lamps and bamboo/wood fires that were kept burning all night long. Looking down on the work area at night made it appear they were working in the “jaws of hell”. Thus, the workers called it “Hellfire pass.”The relentless beatings on the POWs and laborers by the Japanese succeeded in finishing the bridge in 16 months instead of five years as expected. But what was the price for building this railway? The project cost the lives of approximately 15,000 prisoners of war and 100,000 civilians as a result of sickness, malnutrition, exhaustion and Japanese brutality.

During that time there were no modern equipment available for railway work. Instead, the earth and rock were broken by shovels, picks and chunkels (hoes), and carried away in baskets or sacks through human labor provided by the POWs and the Romushas. Embankments of stone were constructed by hand, and metal taps and sledgehammers were used to drill holes for explosives to clear the jungle. Most of the bridges along the railway were timber trestle bridges made from timber cut in the surrounding jungle.

From April 1943, the work pace increased greatly as the Japanese strove to meet a proposed August deadline for completion. This was the notorious “speedo” period. POWs and Asian laborers were punished for any type of misdemeanor or disobedience. Guards inflicted many types of punishment as their superiors ordered. Punishments ranged from face slapping to severe bashings, and often men were forced to hold large rocks of heavy tools above their heads for hours at a time and were beaten if they grew too weary to carry on. During ‘Speedo’, guards beat sick men out of hospital beds to get them to work, and on the work site men were subjected to many beatings. When the POWS and the Romusha worked during the wet season, there were many outbreaks of cholera that claimed thousands of lives.

Of the 60,000 Allied POWs who worked on the railway, 12,399 (or 20%) died. Between 70,000 and 90,000 civilian laborers are also believed to have died. The reasons for this appalling death toll were the lack of proper food, totally inadequate medical facilities and the brutal treatment of Japanese guards and railway supervisors.

Rice, with left-over vegetables and dried fish, was the basic food of the POW. This meager diet provided by the Japanese was supplemented to some extent through trade with local people who gave bananas, green vegetables or any fruits to the Japanese soldiers and the POWs. However, food was always scarce, and starvation led to many diseases, like dysentery, malaria, cholera, beriberi and pellagra. The POWs’ health weakened day by day living in appalling conditions, battling humidity, rain, snakes, and the elements, and facing malaria, dysentery, cholera and tropical ulcers.

POWs lived in “attap” which was a woven palm thatch and bamboo huts. Huts were overcrowded and the cooking and sanitary arrangements at camps were very primitive. Lack of clothing and footwear increased the risk of illness.

The Asian laborers (or “Romusha’” as they were known) fared even worse. Unlike the POWs, they had no Army doctors to give them basic medical treatments. They were left to die in the work site or in the jungle from malnourishment, sickness or exposure to the elements. As a result 90,000 civilian laborers died building the railway.

POWs labored 14 – 18 hours a day despite their fatigue, illnesses, poor diet, and unhealthy living conditions.

Ostensibly, working on the railway for prisoners of war and Romusha was a struggle and a battle for survival. To many prisoners and laborers building the railway under duress, threat of harsh punishment, poor health, living conditions, and diet, death became a normal part of everyday existence. To continue living required every ounce of determination, inner strength, will power, and even luck. These brave souls kept working literally until they dropped. Most were determined they would live to return home. Others struggled to live, even wracked with disease and dying, while many just gave up and wished their death could be sooner. Men kept working till they dropped dead on the tracks. Doctors fought hard for those who retained the will to live and continued caring for the dying. But the only way to stop the dying was to complete the railway.

The mental and physical effects of their ordeal had a lingering post-war effect . Many found it difficult to adjust to normal civilian life and most continued to suffer from a range of conditions attributable to poor diet and harsh treatment in captivity during the war. They were all suffering from PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) from their cruel treatment working on the rail lines. Many ex-prisoners of war published their diaries or wrote about their war experiences, spreading understanding of the experience and helping themselves to come to terms with its impact on their lives.

The Kanchanaburi Cemetery of POWs who died building the railway from Thailand to Burma.

In honor of those who perished while building the railway from Thailand to Burma during their long captivity, the Kanchanaburi Chungkai and Thanbuyzayat cemetery was constructed in Thailand. It is located about 2 hours north of Bangkok. The cemetery, the largest of three on the Burma-Thailand Railway, is located near the site of the former “Kanburi” Prisoner of War Base Camp through which most prisoners passed on their way to other camps. The cemetery, designed by Colin St. Clair Oakes, was created after the war by the Army Graves Service who transferred graves into it from camp burial grounds and solitary sites all along the southern half of the railway and from other sites in Thailand. More than 5,000 Commonwealth and 1,800 Dutch casualties are commemorated in the cemetery, including some 300 men who died of sickness.

The Hellfire Pass was lit up all night to allow POWs worked all day and night.

The Hellfire Pass – current view of the pass through which visitors can take a 4 km walk.

There are many stories of struggles and human triumphs that occurred after the building of this railway system. One such story is Tom, an Australian who enlisted in February 1941, when he was just 17. He served as a corporal with 22 Brigade Headquarters. Captured as Singapore fell in February 1942, Tom served a three-year stint as a POW with A-Force, working mostly on the construction of the Burma-Thailand railway. During this time Tom was interned in ten different camps, contracting malaria and dysentery. Later, at the 55 kilo ‘hospital’ camp he worked as a medical orderly tending other POWs. Forty years after working on the railway, Tom made a decision to return to Thailand to locate Konyu cutting (Hellfire Pass). In 1984 he was not only successful in locating Hellfire Pass but also inspired to preserve this significant site in memory of all those who suffered and died while constructing the Burma-Thailand railway. Tom approached the Australian government to have Hellfire Pass dedicated as an historic site. Initially, funding was provided to build a memorial, formally dedicated in 1987, and increase access to the site. In 1994, further funding was allocated to build the Hellfire Pass Memorial Museum, walking trails and information displays. The Museum was officially opened on April 25, 1998 and now receives over 80,000 visitors each year.

The Memorial commemorates the suffering and sacrifices experienced by those Allied prisoners of war and Asian forced laborers who suffered and died on the Burma-Thailand railway from 1942-1945.  The Memorial acknowledges the suffering and sacrifice by Allied prisoners of war elsewhere in the Pacific during WWII. The Memorial provides an important educational function for the people of Thailand and visitors from Australia and other countries. The Memorial stands as an enduring symbol of the close relationship between Thailand, Australia and those nations whose citizens worked on the Burma-Thailand railway.

The Memorial acknowledges the suffering and sacrifice by Allied prisoners of war elsewhere in the Pacific during WWII. The Memorial provides an important educational function for the people of Thailand and visitors from Australia and other countries. The Memorial stands as an enduring symbol of the close relationship between Thailand, Australia and those nations whose citizens worked on the Burma-Thailand railway.

A. Learning new vocabulary – Choose the correct meaning of these words from the story.

B. Vocabulary usage – Choose (or write) the correct word to complete the sentences in the following exercise.

C. Using “cause and effect” with subordinators “because, since, as, and that”

Using “cause and effect” sentences to give reason for doing something.

In practically every language “cause and effect” sentences are uttered, communicated, and used more often than any grammar concept due to the nature of the events that surround humans. For this reason “cause and effect” sentences need and are important to be learned and mastered to improve on one’s English skills. The most common subordinator used for “cause and effect” is “because” followed by since and as. The most important thing to remember is that the subordinator “because” explains the “reason” for what happens in the main clause. The same is true for “since and as” because they give the reason for doing something. Keep in mind that subordinators are used to introduce “adverb clauses”that show “cause and effect.” Also, understand that adverb clauses have a subject and verb but are dependent clauses that cannot stand alone as a sentence.

For example: George bought a new house for his family because he was able to save enough money and his family was getting bigger. (The reason George bought a new house was because he was able to save enough money and his family was getting bigger.)

Using “as and since” gives reason for doing something.

Examples:

- Since I bought a new Gibson guitar, I have been able to play my favorite songs with enthusiasm and energy.

- As I learned how to create new sound effects on my new Gibson guitar, I started composing original music to accompany the new sound effects I had discovered.

Using “that” as a “cause and effect” subordinator also creates the same meaning of “because.”

Example: I am so glad that I bought a new Gibson guitar.

My parents were furious that I bought an expensive Gibson guitar.

As you can see the subordinators “because, since, as, and that” function as “reasons” for doing something.

Exercise on using “cause and effect” sentence to show a reason for doing something.